Could the US win the AI race, but lose the war for economic preeminence?

(Here is a piece I wrote for the Financial Times about the geopolitics of artificial intelligence. If you are still looking for a Christmas or Holiday gift, consider my new book "The Age of Extraction" recently on New Yorker Magazine's list of best books of 2025).

Over the past year, major US tech companies have spent more than $350bn on AI-related infrastructure, with projections of over $400bn for 2026. This far exceeds the spending of any other nation — most notably China, where total investment is closer to an estimated $100bn. For many in the West, it may be reassuring that we have companies bold enough and capital markets deep enough to dominate a spending contest. If artificial intelligence is — as prophesied — the one ring to rule them all, then it would seem the west has the future in hand.

That is the optimistic story. Yet there is another possibility: that Silicon Valley’s obsession with AI could mean winning the AI race but losing a broader contest for economic pre-eminence. That follows because the US has gone all-in on AI, while China is spreading its bets across several plausible futures. It all depends on the bet on AI being the right one. Despite all the talk of an existential AI race, China is somewhat less committed to AI than sometimes portrayed. Beijing regularly describes AI as a “national strategic priority” and has invested to avoid falling too far behind. But the state and its major companies are spending much more money to secure dominance in other domains, such as electric vehicles, batteries, robotics, solar panels, wind turbines and other forms of advanced manufacturing. These sectors may be less glamorous, but their returns are far less speculative.

It is the US that is truly infatuated with AI, with investments influenced by goals that are as mystical as they are commercial, especially the pursuit of Artificial General Intelligence and “the singularity”. There is a strong belief in continued exponential progress — a rarity in the history of technology. The deeper one digs, the more otherworldly it becomes, among both AI proponents and doomsayers. The concentrated, monopolised nature of the US tech sector adds to the risk: with so much spending power in so few hands, the danger of groupthink grows.

What to do? If the pay-off from AI is uncertain, the prudent strategy would involve diversification and hedging. But American venture capital is as fixated on AI as the tech platforms themselves, and financial markets have rewarded the current course. The public sector could hedge, but the US — under Trump — has cut back support for clean-energy investment, leaving the national tech strategy looking like a large wager on a single horse. Today’s AI spending, while impressive, is undeniably a frontloaded bet on one vision of the future. It may prove inspired and visionary. Or it could be remembered as an overdone fixation on a technology whose utility is narrower than advertised. Its failure to deliver could also be the trigger for a destabilising stock crash that leaves the west behind.

Seen from some distance, the American tech strategy looks like a straightforward syllogism: AI is the most important technology of the 21st century; it is extremely expensive to build; therefore, whoever spends the most will be the dominant civilisation of the future. But any syllogism stands or falls with its premises. The key question is whether today’s version of AI is in fact the most important path to prosperity and a better future. That turns out to be more of a leap of faith than many assume.

The business case has long been somewhat vague, and on closer examination much of what Silicon Valley presents as the goals of AI has a distinctly fantastic flavour. “We believe Artificial Intelligence is our alchemy, our Philosopher’s Stone,” writes venture capitalist Marc Andreessen. He and Silicon Valley’s other “accelerationists” believe achieving artificial intelligence is the paramount goal for humanity, a kind of secular rapture. Believers think AI can solve most of our problems: just last week, Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis suggested AI could invent free renewable clean energy and discover the cure for most diseases; humanity is then “travelling to the stars and spreading consciousness to the galaxy”.

In some ways, the American AI race looks not unlike the race to build the grandest cathedrals in late medieval Europe. Then, the motives were a mixture of pride, economics and a sincere religious belief the structures would bring humanity closer to salvation. The byproduct was some extraordinary architecture — but also financial ruin for cities such as Beauvais and Cologne, overwhelmed by their own ambition.

Inside Silicon Valley, the finish line of the “race” is the achievement of AGI: the moment when machines acquire humanlike cognitive versatility. Believers argue that once AGI arrives, it will trigger further breakthroughs — the “law of accelerating returns”. A superintelligence may then reach “the singularity”, a concept popularised by Ray Kurzweil and Vernor Vinge, ushering in a regime described by the latter as “as radically different from our human past as we humans are from the lower animals”. Accelerationists hope this superintelligence will yield a “radical abundance”. As Sam Altman once said, once general AI is invented, “poverty really does just end”.

Andreessen, the author of a “techno-optimist manifesto”, puts it his way: we are “poised for an intelligence takeoff that will expand our capabilities to unimagined heights”. The technology, he claims, is “liberatory of human potential. Liberatory of the human soul, the human spirit. Expanding what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive.” It follows, on this view, that slowing AI development is not merely unwise but immoral. “[A]ny deceleration of AI will cost lives. Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.”

By comparison, at least, the way the Chinese government speaks about AI is more modest. Yes, China’s economic leadership views AI as a priority and has boldly claimed it seeks to lead the world by 2030. Yet the rhetoric lacks the eschatological tone common in Silicon Valley. Chinese economic planners appear more interested in AI as a tool for industrial processes than as a means of creating a superintelligence that will reach the singularity. The State Council’s 2025 “AI+” initiative is focused entirely on efficiency-enhancing applications rather than intelligence explosions.

There is another important difference. China is banking far more heavily on simpler, lower-cost open-source AI models. In the US, most of the leading “frontier” AI models are secret and proprietary, in part as a business model and in part due to the apocryphal fears that the wrong actors could trigger human extinction. The smaller, lower-cost Chinese models may be seeking, in that sense, to be the more nimble 1970s Toyota rivals to the giant American cars produced by General Motors.

More importantly, China is hedging its bets by investing heavily in a wide range of other technologies that might reasonably be described as “the future”. In 2024, the country invested an estimated $940bn in clean-energy capex, broadly defined as renewables, electricity grids and energy storage (batteries), dwarfing its AI investments. In these sectors, AI is meant to be a complement — the glue rather than the structure.

While China’s overall economy remains weaker than it was in the 2010s, elements of this broader strategy seem to be bearing fruit. Last year, 70 per cent of the world’s EVs were manufactured in China. China also accounts for roughly 80-85 per cent of global solar photovoltaic manufacturing, and more than 75 per cent of all global battery production. If we set AI aside for a moment and assume that these technologies represent the future, it is clear who is ahead.

The popular notion of an international AI race, and of a Chinese state gripped by existential obsession with AI, seems to come more from American sources than Chinese. In a 2020 paper, for example, political scientist Graham Allison and former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt argued that China desperately needs to develop AI to prevent the collapse of its state-planned system. “The command of 1.4 billion citizens by a Party-controlled authoritarian government is a herculean challenge,” they wrote. “AI could give the Party . . . a claim to advance a model of governance — a national operating system — superior to today’s dysfunctional democracies.” In essence, the need for social control was said to leave China no choice but to invest heavily in AI.

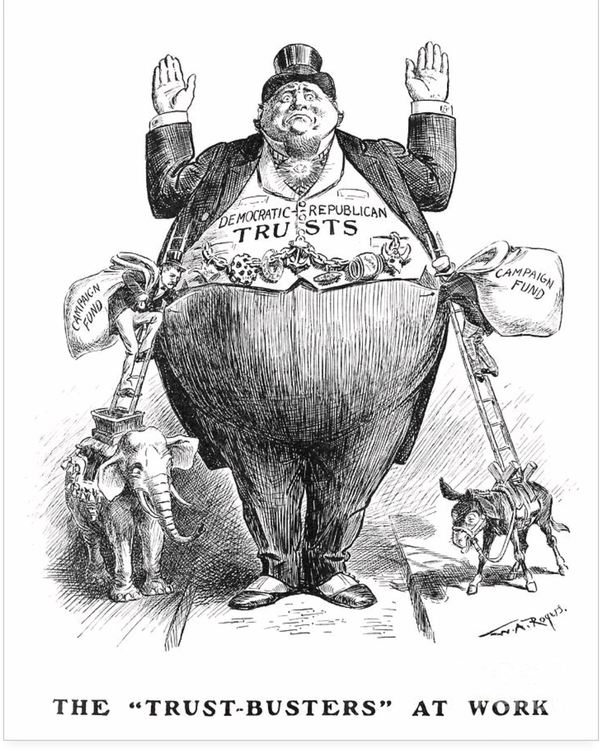

The theory is clever, but whether it is right is another question. What is clear is that the Party believes economic performance is essential to its survival, but, as described above, that conviction has led it towards a diversified strategy, not a single bet on artificial intelligence. Frontier AI, the most expensive form, has not been the main emphasis, and China appears to think it can do what it needs with “good enough” AI. The success of DeepSeek — a decent domestic copy of ChatGPT — may validate that strategy. The US-China “AI race” does serve another function: it is an excellent messaging and lobbying tool for the American tech industry. Schmidt, Mark Zuckerberg and others have insisted that government intervention such as antitrust enforcement would handicap the US in this end-of-times battle for civilisation itself. The idea of a race also justifies extraordinary levels of spending, lest someone else swoop in and take the prize.

It is probably more accurate to say that the real AI race is an American race that dates from the 2010s — with China added to the narrative later. In the US, this contest moved from academia to commerce when Google began aggressively buying up AI talent and firms, including Britain’s DeepMind and Geoffrey Hinton’s DNNresearch. The race was joined in 2015 when Elon Musk and Sam Altman agreed on the need to fund non-profit OpenAI as a rival to Google. And that American race was from the beginning more eschatological than commercial. Ray Kurzweil in 2005 set 2045 as the date for the coming singularity; hired by Google, he in 2017 asserted that “we will multiply our effective intelligence a billion fold by merging with the intelligence we have created”. Musk, meanwhile, became obsessed with the dangers that superintelligent AI “could render humanity extinct”. From the beginning, extravagant, end-of-history rhetoric has been the hallmark of the field.

Unlike in China, the American doubling and tripling down on AI has coincided with a move away from investment in clean-energy technologies and a reduction in support for basic research in other fields. The Trump administration has worked to de-incentivise electric vehicle uptake and clean-energy investment, and in response GM and Ford have reduced their investments in EVs and battery production. The US has further reduced spending on basic science, now at roughly one-third of its 1960s level, and has waged rhetorical war on major academic research universities such as Harvard and Columbia. With the federal government reducing its commitment to science and clean energy, the American bet on the future increasingly looks like artificial intelligence or bust.

I would not deny the possibility that the accelerationists are right and that we may yet achieve an AGI that works for the betterment of humanity. If so, this period will be remembered for its brilliant grasp of what was needed to elevate humanity into a new and better age. But that outcome is far from certain, and both history and physics suggest caution.

Moore’s law — the observation that the number of transistors on a chip doubles roughly every two years — was an exception. For most technologies, after an initial inventive burst, the rate of progress begins to level off and further investment yields diminishing returns. The lightbulb was a giant improvement on the candle, but the next decade of innovation was comparatively incremental. Physics has a stubborn way of limiting exponential improvement: the speed of air travel, to take an obvious example, has not increased since the 1960s; and the efficiency of nuclear reactors, similarly, has improved only incrementally since the 1970s.

Contemporary AI based on neural networks and deep learning has undoubtedly undergone extraordinary, disruptive improvement over the past decade. But over the next decade, progress may become more incremental, or run into new limits. Some constraints may arise from a scarcity of patterned data from which to learn, the sheer amount of energy required, or the computational challenges created by the physical world. The undeniable truth is that we simply do not know where we are on the curve — and anyone who claims otherwise is making things up.

The bet that AI will continue to improve exponentially is therefore uncertain, and the concentrated, monopolised nature of the current tech industry adds to the problem. Spending decisions have become highly centralised — the decisions of just a few companies, in a manner more usually associated with state planning — and groupthink is a real danger. The stock market, which has richly rewarded those investing in AI despite the vague business case, is not yet serving as any kind of check.

Even if the all-in AI strategy is risky, might the spending still be defensible? One defence is cultural: Silicon Valley has a habit of going wildly overboard on new ideas, but even overshooting the mark may be better than being too cautious. Alternatively, it can be argued that spending on almost anything is preferable to hoarding profits or channelling them into stock buybacks. One estimate suggests that over the past 10 years the IT sector has spent more than $2.1tn on buybacks; arguably, spending that money on any genuine capital projects is better for the economy than spending to inflate share prices. From this point of view, the money could be used to build Mars rockets or elaborate amusement parks, so long as it is actually spent.

Another defence of AI spending is more ominous: that the big talk is just that, and the real objective is for existing tech monopolies to build a deeper moat around their current businesses. Amazon’s $2.45tn market capitalisation, to take one example, is a prize many would-be challengers would love to claim a part of, and AI could be the agent of industrial succession. On this view, Big Tech’s AI splurge is meant to forestall a challenge from AI start-ups. That’s a story that has much less to do with US-China competition than with the desire of powerful companies to entrench their position.

It is, in other words, best understood less as an investment in humanity, and more as an investment in corporate immortality.