Netflix? Paramount? What should and what will happen with Warner Brothers

(This is Tim Wu with a note on the Warner Bros merger. My new book The Age Extraction is a great present for any policy wonk or tech critic in your family, and was just named one of New Yorker Magazine's best books of 2025.)

This week, two prominent media firms — Netflix and Paramount — have begun fighting it out to try to take over Warner Bros. Discovery, the company that owns HBO, the Warner Bros. film studio, CNN, Discovery and a lot of other media properties.

If you want to know what should happen, and what will happen, read on.

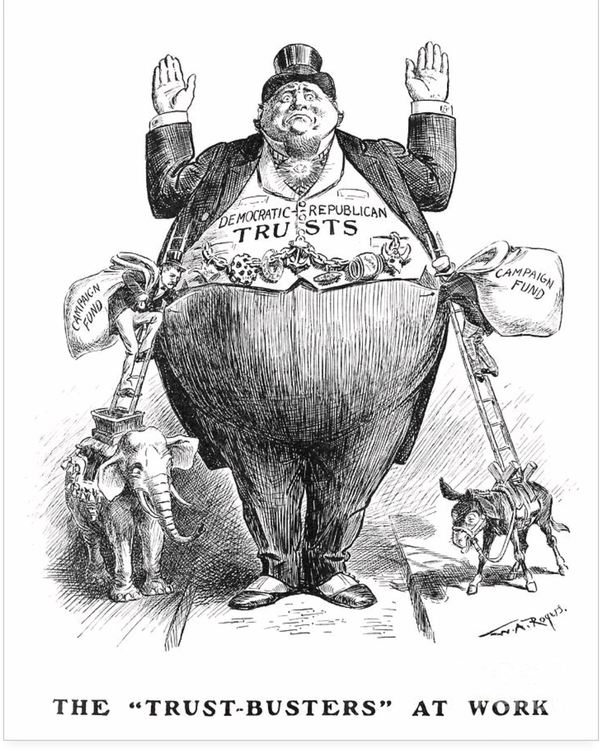

Start with the fact that both mergers are presumptively illegal. The Clayton Act of 1914, the second of the United States’ major antitrust statutes, bans acquisitions and mergers when the effect “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” Under the guidelines of the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department, both mergers appear to “raise a presumption of illegality.”

But isn’t this really about politics? And should that influence how you think?

Some argue that the Netflix deal deserves support anyway because Paramount would be an even worse buyer. The idea is that David Ellison, the chief executive of Paramount, wants to build an evil media empire using his father’s money and gut CNN, which Warner Bros. Discovery owns. Mr. Ellison’s father, Larry, is one of the world’s richest men and a major Republican donor close to President Trump.

Basically, the idea is that one should cheer on the Netflix deal because otherwise the son of a friend of Trump will benefit.

I can see the temptation to think that way, but you can’t run a rule-based system like that. You can’t look at every merger and try to decide whether it benefits or hurts friends of Trump — that just makes the law revolve around him.

The better view is to recognize that both deals would be bad for the country, and both should be challenged by antitrust authorities. Warner Bros. Discovery’s streaming business is actually profitable as it is. It should just stay independent. And Warner Bros., if you must sell, maybe try finding a buyer who is not a direct competitor?

The fact is that Netflix’s proposed merger with Warner Bros. Discovery would be damaging not just in economic terms but also in terms of cultural creativity. In the long run, buying Warner Bros. would probably be as harmful for Netflix as it would be for Warner Bros. The combination of close rivals usually works out that way.

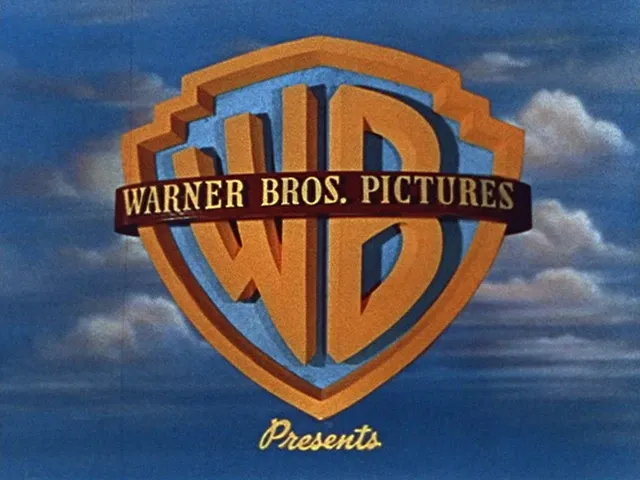

Since its founding in 1923, Warner Bros. has made bold business and creative bets. In the late 1920s it was the first major studio to do sound films. It was one of the few to bet heavily on television in the 1950s. In the 1970s the larger Warner company pioneered superhero films, and starting in the late 1990s its HBO division essentially invented premium television with shows like “The Sopranos” and “The Wire.” Many of its gambles have been contrarian, such as developing Looney Tunes as a goofier, more anarchic alternative to Disney’s animation. That is what competition is supposed to do: force companies to carve out a niche for themselves.

Netflix, for its part, is the greatest media innovator of the past decade. Transcending its modest origins as a DVD-by-mail service, it managed to succeed where earlier efforts to mix the internet and entertainment industries failed (such as Microsoft’s). Netflix proved that streaming could be a viable business model. It also, for better or worse, pioneered the binge-release model (with “House of Cards”) and so-called global originals (like “Squid Game”).

If Netflix and Warner Bros. Discovery were combined, it might be a cash cow, but the whole would be less than the sum of the parts. Netflix has suggested that it might keep HBO separate, but what parent company lets itself be outbid by its own unit? The more likely outcome is a bland mush — the loss of a distinct sensibility within either operation.

A Paramount acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery would not be better. In addition to having a significant overlap in streaming services, Paramount and Warner Bros. are direct competitors as major film studios with theatrical releases. Their merger, at least on those grounds, is also presumptively illegal.

For those who want a more technical analysis: antitrust enforcers would point out that the two companies are direct competitors in premium streaming services, where Netflix is No. 1 and HBO-Discovery is No. 3 or 4, depending on which ranking system you use. Merging them would eliminate a head-to-head rival. That hurts consumers by making price increases easier, and it hurts sellers of films and TV by combining bidders. When the next equivalent of “The White Lotus” is being pitched, you expect Netflix and HBO to compete for it. Eliminating one of the two is pretty much the textbook antitrust definition of lost competition.

So what will happen? I predict, either way, court challenges that last a year. It isn’t clear right now who will win the battle to acquire Warner Bros. If it is Netflix, a federal challenge seems a near certainty, and I’d put the odds at greater than 50 percent that Netflix will lose — but it will take time.

If Paramount wins the takeover battle — and if the federal government does bow out (perhaps, as some fear, because of an affinity between Mr. Trump and the Ellisons), something else may happen. California may well bring the challenge to protect workers in the film industry. California’s attorney general, Rob Bonta, has been an active enforcer of the antitrust laws, so I think there are strong odds he sues to block a Paramount deal if the federal government folds.

Why is Warner Bros. Discovery even selling? It is spinning off its cable channels, so the answer has little to do with its core business — the streaming divisions are profitable — and more to do with the burdensome costs of its previous inadvisable mergers. The disastrous acquisition in 2018 of Warner Bros. by AT&T (and the foolish failure of a judge to stop it) began the process. AT&T then spun off Warner Bros. and combined it with Discovery in 2022, saddling the merged company with billions of dollars in debt from merger financing. Ego-driven, hype-influenced decision-making — the curse of the mogul — has created this mess, not business fundamentals.

Warner Bros. Discovery still makes money with entertainment that millions of Americans want to watch. After it finds a noncompeting buyer or collects the $5.8 billion fee that the offer requires Netflix to pay if regulators scuttle the deal, it should be in a good position to rise again.

(A version of this post originally appeared in the New York Times).